Region’s residents celebrated finally crossing Interstate 5 Bridge for free after years of discussion, lawsuits

The greatest impromptu celebration in over a decade consumed downtown Vancouver on New Year’s Eve 1928. Cars waiting in anticipation jammed the streets, undeterred by the drizzle and chilly winds, the congestion growing minute by minute.

They celebrated not just the beginning of a new year, but the start of a new chapter in Clark County. As the calendar rolled over, horns, cowbells and the Interstate Bridge siren jubilantly wailed, cheering on the new year and the bridge officially being toll-free.

“She’s free! Let’s go!” one person said.

Tolls cost 5 cents, about $1.15 today, and although they could be paid on the bridge, travelers were encouraged to purchase toll tickets at local stores. (Bridge coins or tokens were used later in the bridge’s history, but not during the first span of tolls.)

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

But miles away, in the northeast corner of the county, Louis Tyson, a toll-free bridge opponent, celebrated something else. His lawsuit challenging the removal of tolls from the Interstate Bridge had been successfully appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States and it was set to be ruled on in the new year.

Nearly as quickly as the bridge opened in 1917, the question over eliminating tolls became a heated topic of conversation. There were setbacks and false starts, and stringent opposition, but after nearly 12 years they were removed.

Although many Clark County residents today are unfamiliar with tolls, the region is not. Tolls were used to fund the construction of both spans of the Interstate Bridge and are slated to pay for one-third of its replacement.

The Interstate Bridge

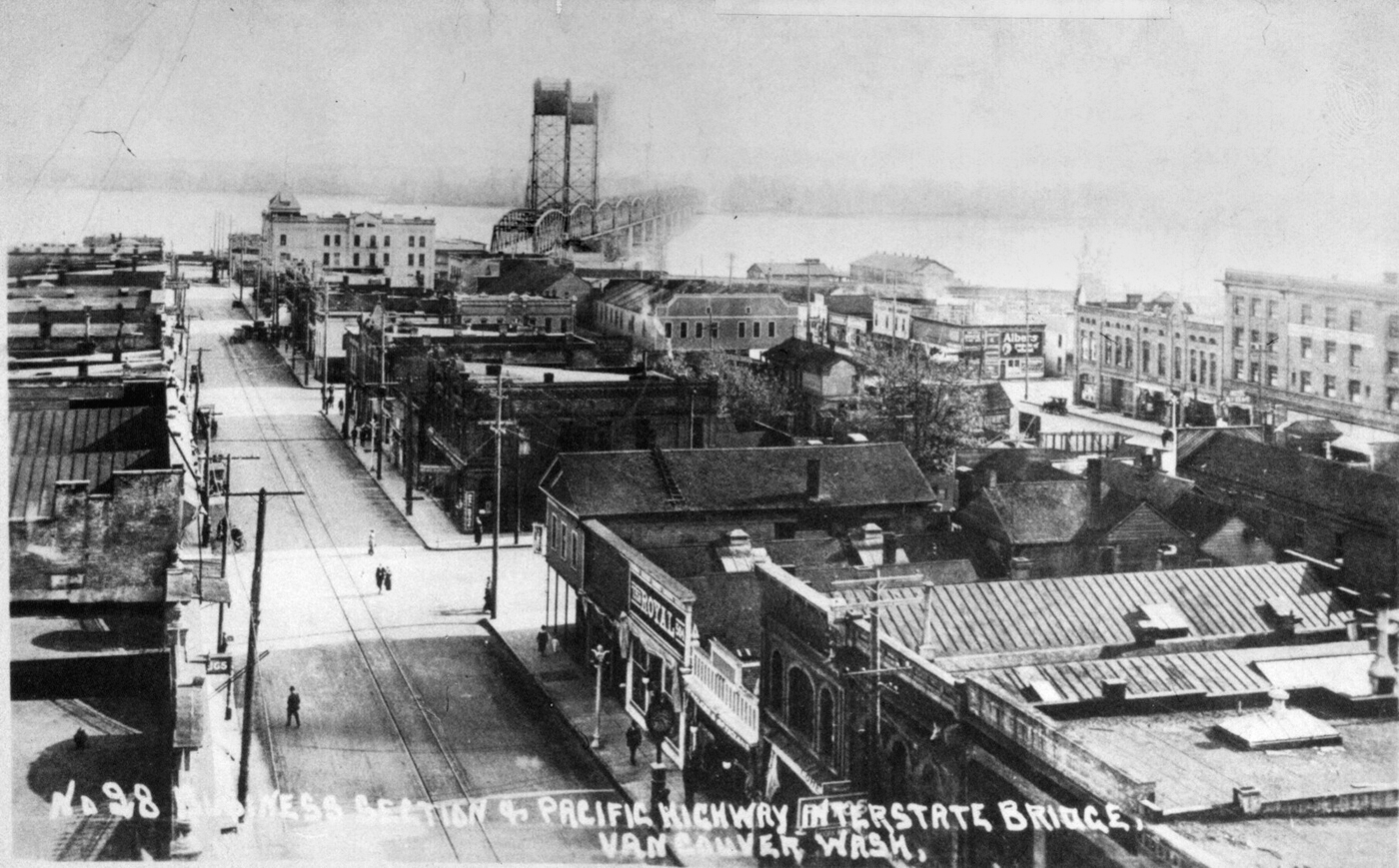

On Feb. 14, 1917, nearly 50,000 people celebrated the opening of the Interstate Bridge. At the time, Vancouver’s population was only 12,000.

Within the first two weeks, about 52,000 people crossed the bridge via foot, bike, car and trolley. The streetcar was the most popular form of transportation, however. Streetcars crossed the bridge 2,096 times in the first two weeks and carried more than 33,000 people.

Because tolls were paid by the person and not the auto, some attempted to avoid them by hiding in the trunk.

Tolling proved profitable too: it netted $3,722 in tolls, about $86,000 in today’s dollars, within the first two weeks.

The new bridge, with its wide and smooth roadway, became a magnet for speed racers and traffic cops alike, according to articles in The Columbian from the time. A robber dubbed “the bridge bandit” held up the bridge twice in 1920 before being caught.

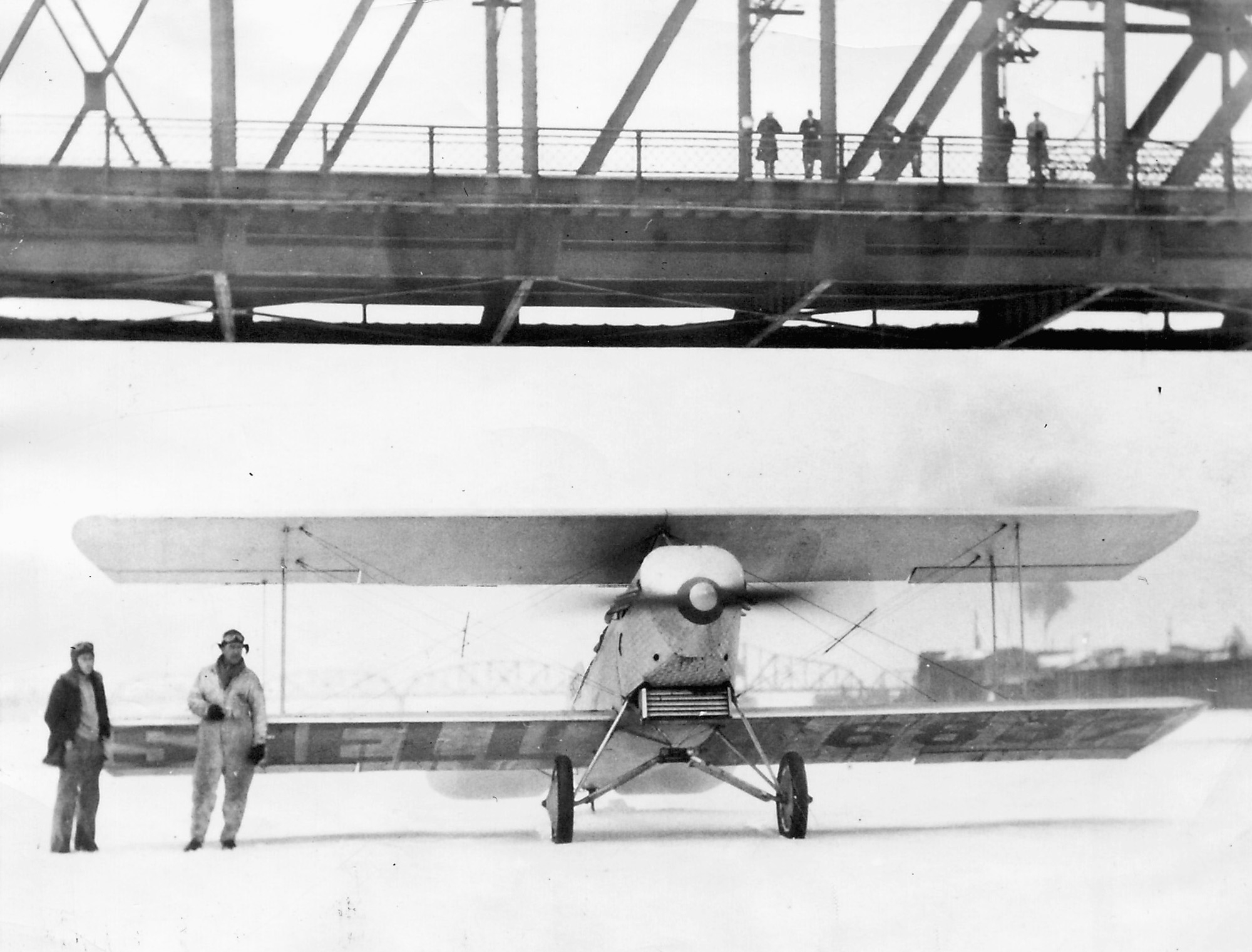

There were only a handful of times when people on foot and by wheel could cross the river without the bridge or by boat: The river froze in 1918 and 1930 to the point that people could walk and, in 1930, drive across. In 1919, ten prisoners in the county “were given an outing” to de-ice the bridge.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

World War I

Hysteria from the Great War was at an all-time high, even with Vancouver’s bridges.

In the months before the United States entered World War I, the railroad bridge downstream from the Interstate Bridge was so critical to transporting supplies for the war effort, that Oregon’s governor called for the National Guard to protect it from potential sabotage.

Although no orders were given to protect the Interstate Bridge, The Columbian at the time hypothesized that guards and police officers would tail suspicious individuals to ensure the bridge remained safe.

“From now on, whether troops are put on guard or not, everyone crossing the bridge will be watched,” The Columbian wrote.

A month later, Vancouver’s worst fears were nearly realized.

A man suspected of being a German spy carried a package toward the Interstate Bridge. Police officers were alerted and tailed him. The suspected spy, aware of the officers following him, became wary and ran toward the bridge, clutching his package tightly.

Police apprehended him and, upon cautiously opening the package, they discovered a new pair of shoes. The reason he was suspected of being a spy: he had purchased a pail of sauerkraut that morning.

The anti-German hysteria was at a high level, and Vancouver was on edge. Anyone loitering on or near the bridge could have been suspected of being a spy. In April 1917, two well known community members who often strolled at the waterfront and watched the ferries through a spyglass were falsely arrested and accused of being spies.

The hysteria died down with the Armistice in November 1918, and normal life resumed, and with it, a renewed focus on the Interstate Bridge.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

False starts

Although tolls were a nuisance to many, they were seen as necessary in the creation of an Interstate Bridge. After Washington Gov. Ernest Lister vetoed a bill funding a bridge in April 1913, Clark and Multnomah counties were forced to fund and build it on their own.

“The overwhelming majority of the people of this county are making no complaint about the tolls, but are well satisfied with the present arrangement,” The Columbian reported in 1918.

The toll money went to paying off the bonds and paying bridge employees. Surplus money went toward improving highways throughout the county.

Within a year and a half of the bridge’s grand opening, talk about removing tolls began to percolate. Multnomah County’s preference was to remove tolls, however, Clark County could not afford to without placing a significant burden on its residents — or unless Washington paid off a sizable share of the bonds.

The rumbles grew louder. In January 1919, it was briefly thought by many that Washington and Clark County would reach an agreement where Washington would pay for half of Clark County’s bonds and eliminate tolls. Clark County’s commissioners unanimously shot the idea down, stating in a letter in The Columbian that they will only consider selling the bridge for its full value.

But it did not stop the toll-free crowd. Over the next decade, the question became when — not if — tolls would be taken off the bridge.

“The toll system is a leftover of a by-gone age,” The Columbian wrote in 1922. “The stranger coming across the Interstate Bridge is sure to feel that communities that maintain this out-of-date method of taxation has lost step and fallen behind other communities.’’

The tolls were cited as hurting industry and preventing a “location otherwise ideal,” as The Columbian said, from flourishing. The Concrete Pipe company was one of a handful of companies to move, citing the bridge’s tolls as the primary reason.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Economically unsound

A report filed by the Washington State Highway Commission in January 1927 recommended that tolls be removed from the Interstate Bridge, reasoning that they were economically unsound. The logic went, if the tolls just affected Clark and Multnomah counties, they would be acceptable; but because the bridge links Canada to Mexico and affects two whole states, it is a tax on everyone.

A unanimously approved resolution asking Clark County legislators to secure an appropriation of $250,000 from the state for Clark County’s share of the bridge and for tolls to be removed by July 1928 was adopted by community leaders just one day after the highway commission’s report.

Support for the resolution came with three stipulations. One, the Legislature had to appropriate $250,000; two, Clark County residents had to approve it in a June special election; and, three, Multnomah County had to sell its share to Oregon.

A hurdle was cleared two months later, when both chambers of the Washington Legislature passed a bill appropriating $250,000 for the purchase of the bridge. It was signed into law by Washington Gov. Roland Hartley less than two weeks later. All that was left on Washington’s side was for the paper to be signed.

But as summer came and nearly went, the paperwork never arrived. The state claimed they mailed it, but Clark County never received it. What happened was someone in the governor’s office confused the Interstate Bridge with the Pasco-Burbank toll bridge in Eastern Washington and accidentally mailed it to Pasco. They quickly corrected the mistake.

With the funding already appropriated by the Legislature, the Clark County commissioners decided to cancel the special election, calling it superfluous.

Near the end of the year, Multnomah County and Oregon agreed to terms for Oregon to buy the bridge, and, with that, tolls were set to be removed by Jan. 1, 1929.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Path to the Supreme Court

Days before the bridge was set to be toll-free, Louis Tyson, a Chelatchie Prairie farmer, spearheaded a lawsuit to prevent the sale of the bridge. He was aided by pro-toll activists on both sides of the river.

The activists argued that the bridge could not be sold without the approval of Clark County voters, and that the 1927 appropriation of $250,000 authorizing the purchase was illegal under the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution.

Tyson unsuccessfully ran for county commissioner earlier that year, proposing that the entire system of taxation be changed, leading to The Columbian writing in an editorial that “the poor fellow didn’t know, apparently, whether he were running for county commissioner or the Legislature.”

The lawsuit was regarded as a last-ditch attempt to prevent the sale of the bridge and of being built on a dubious legal argument. A temporary restraining order was put in place prohibiting the sale of the bridge for one week, until Dec. 24, 1928.

The federal district court ruled that Tyson was without jurisdiction in the case on Dec. 22. Tyson was unconcerned; it was merely a step toward the Supreme Court of the United States.

Multnomah and Clark counties were undeterred, however. After Multnomah County’s legal adviser said there was no legal barrier to the sale of the bridge, the Multnomah County commissioners signed a document transferring the county’s interest to the state of Oregon, ensuring the bridge would be free by the New Year.

There was no time for a formal celebration to be planned, but the entire town felt a sense of elation not equaled since the Armistice.

“Every motorist within easy range, in fact, will feel the impulse to celebrate by driving as free as air across the bridge that has been a barrier to him ever since it was built,” The Columbian wrote.

With the new year, many crossed the newly free bridge. Some tried to be the last person to ever pay the toll while others tried to pay the toll out of habit.

Tyson’s case reached the Supreme Court on April 22, 1929. In spite of the glee and appreciation of not having to pay tolls, The Columbian detected no alarm among Clark County residents.

The court found, as Chief Justice William Howard Taft announced, that it did not have jurisdiction and ordered the appeal dismissed.

“The Chelatchie Prairie farmer, it will be remembered, threw a bombshell into the proceedings by filing his suit Dec. 3, 1929,” The Columbian wrote. “However, the explosive which electrified Clark and Multnomah counties and threw panic into some observers proved to be a dud.”

Tolling, by the time it was removed, regularly netted over $500,000 in profit annually, nearly $9 million in today’s dollars.

The bridge was finally toll-free, but with Clark County’s population on track to triple by the 1960s, its single-span would not be capable of serving a vastly bigger region.

Spanning History:

The long history of the Interstate 5 Bridge

Part 1: Interstate Bridge: History of conflict, compromise

Part 2: Interstate Bridge toll removal starts new chapter

Part 3: Coming in 2023

This story was made possible by Community Funded Journalism, a project from The Columbian and the Local Media Foundation. Top donors include the Ed and Dollie Lynch Fund, Patricia, David and Jacob Nierenberg, Connie and Lee Kearney, Steve and Jan Oliva and the Mason E. Nolan Charitable Fund. The Columbian controls all content. For more information, visit columbian.com/cfj.

This story was made possible by Community Funded Journalism, a project from The Columbian and the Local Media Foundation. Top donors include the Ed and Dollie Lynch Fund, Patricia, David and Jacob Nierenberg, Connie and Lee Kearney, Steve and Jan Oliva and the Mason E. Nolan Charitable Fund. The Columbian controls all content. For more information, visit columbian.com/cfj.

For more history of Clark County visit newspapers.columbian.com